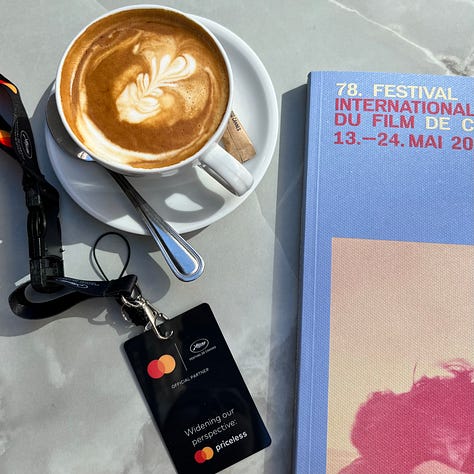

After three unforgettable days at the Cannes Film Festival, which I took some time to digest, I’m excited to share a selection of 10 films that left a strong impression on me. From intimate human stories to explorations of contemporary crises, these films showcase the diversity and boldness that define this year’s lineup. Here are my highlights from Cannes.

1. O Agente Secreto by Kleber Mendonça Filho

This was definitely one of my favorites from this year’s line-up and it was more than worth the over two and a half hours of sitting in a movie theater (the seats in Cannes are pretty confortable as well, which definitely helped). Set in 1977 Recife, this political thriller follows Marcelo, a man with a shadowy past seeking to reconnect with his son amidst the vibrant chaos of Carnival. As he attempts to rebuild his life, echoes of his former existence resurface, plunging him into a web of espionage and danger. Divided in chapters, the film was off to a slower start, introducing mysterious motifs and characters which were not yet linked, before revealing in the latter parts the giant web that was uniting them all in the city of Recife. Bringing together an ex-engineering university professor, his in-laws and son, a network (and neighborhood) of political refugees hiding their identities with the help of an elderly woman named Dona Sebastiana, as well as contemporary researchers looking back into the story through unexpected ellipses, Kleber Mendonça Filho crafts a narrative that delves into the personal costs of political unrest. Filho earned his Best Director award at Cannes, with Wagner Moura deservedly receiving Best Actor for his performance as Marcelo. Although mentioned less in the press and award sessions, the cinematography and graphics were equally memorable.

2. My Father's Shadow by Akinola Davies Jr.

Akinola Davies Jr.'s debut feature is a deeply moving exploration of familial bonds set against the backdrop of Nigeria's 1993 presidential election. This masterpiece was, surprisingly for me, the first Nigerian film ever selected for the official lineup of the Cannes Film Festival. The semi-autobiographical story centers on two young brothers spending a day with their largely absent but loving father in Lagos, navigating the complexities of familial reconciliation amidst a coup d’état and generalized civil unrest. I am not going to lie to you, the film was heart-wrenching, and it left me and my festival-made friends crying over the credits, but the storyline, cinematography, and character revealing—rather than construction—were just spectacular, making this an absolute must-see from this year’s selection. Confirming my feelings and admiration for this film, its intimate and perfectly executed portrayal of personal and political intersections garnered it a Special Mention for the Caméra d'Or at Cannes.

3. The Phoenician Scheme by Wes Anderson

Wes Anderson returned to Cannes with a stylized tale set in the fictional Middle Eastern country of Phoenicia. The narrative follows Zsa Zsa Korda, a flamboyant industrialist embroiled in an ambitious infrastructure project, and his estranged daughter Liesl, a novice nun to whom he legates his entire estate. Together, and with the newly appointed biology-professor-turned-spy, they set on an adventure to secure the funds for Korda’s most treasured project—or “scheme”—involving other just as memorable figures. Anderson's signature visual flair and ensemble cast, including Benicio del Toro, Mia Threapleton, and (finally!) Michael Cera, bring to life a story that satirizes ambition and legacy.

In his interview for the dedicated Cahiers du cinéma edition, published just before the Cannes Film Festival, the director admitted having had the role in mind specifically for Benicio del Toro (already one of his collaborators for The French Dispatch). Incarnated by the Puerto Rican actor, which Anderson described as having the “European” flair so characteristically found in his protagonists, Zsa Zsa Korda’s storyline was intended as a commentary on the excesses of tycoons blinded by money and power. Most notably, his insistance on flying under any unfavorable conditions puts him through numerous plane crashes—which he survives. His personality, on the other hand, has a more personal origin, recalling the Lebanese father-in-law of the filmmaker. An unmissable feel-good moment, echoed by the current Wes Anderson retrospective at the Cinémathèque française in Paris.

4. La Femme la plus riche du monde by Thierry Klifa

I saw the avant-premiere of this film at Palais des Festivals on my first day in Cannes, after queuing for four hours during which I made new friends, watched the cast arrive—led by Isabelle Huppert wearing a stunning green dress and sunglasses—and then walked the red-carpeted stairs ourselves. Sharing the screening with the whole cast and witnessing the ten-minute standing ovation at the end definitely made this my most memorable experience of the festival, and the film itself contributed to this. Thierry Klifa’s dramatic comedy features Huppert as Marianne Farrère, a wealthy (the wealthiest, according to the title) heiress entangled in a complex relationship with a manipulative photographer. With a quintessential French kind of humor as well as occasional dark-background confessionals, the film delves into themes of power, trust, and deception within the upper echelons of society.

Huppert's standout performance, spanning a spectrum of emotions from glacial detachment to rediscovered ecstasy, was seamlessly complemented by a cast including Marina Foïs, Laurent Lafitte (whose acting was so good, it made me physically feel anger towards his character), and Raphaël Personnaz (whose unassuming role as the butler of Mr. Farrère actually turned out to be my favorite). This tale of familial intrigue addresses so many social issues that it would be difficult to mention them all here. What is certain, however, is that it highlights the difficulty of reconciling financial heritage, religious identity, past and outdated political commitments, emotion, and maybe most of all, desire. The diversity of the characters’ personalities, along with the unforeseen progression of the narrative, takes us through them all.

5. Eleanor the Great by Scarlett Johansson

Scarlett Johansson’s directorial debut delivers an emotionally layered film centered on Eleanor, a grieving elderly woman played by June Squibb. The story follows Eleanor as she assumes the identity of her late best friend Betsy, a Holocaust survivor, in an impulsive yet deeply heartfelt attempt to preserve her memory. What begins as an ethically fraught gesture gradually unfolds into the most emotional ode to friendship I’ve seen on screen. Though Eleanor’s impersonation invites controversy, the film argues that the truths she speaks were never hers, but they were never lies either. This ethical tension is gently resolved in the final scenes, when a television host (a sweetly surprising detail: Betsy’s old celebrity crush) recounts Eleanor’s story as one shaped by grief and friendship. It’s a small, imperfect form of justice, but a sincere one.

While the narrative occasionally drifts away from the central bond between Eleanor and Betsy, this apparent detour only strengthens the film’s emotional core: when the friendship returns to the foreground, it does so with shattering clarity. Some of the stories Eleanor shares while impersonating Betsy are indeed wrenching. In particular, one devastating nocturnal ellipsis—when Betsy, plagued by insomnia, recounts how she lost her brother—anchors the film’s exploration of survivor’s guilt. Her quiet conclusion reframes the entire film as an act of love, not appropriation. Having dealt all her life with the question of why it was her that survived and not her brother, in her final moments Betsy expresses an equally heartwarming and heart-wrenching insight: “So that I could share this life with you.”

6. Un Poeta by Simón Mesa Soto

Simón Mesa Soto’s Un Poeta offers a quietly hilarious portrait of a man clinging to the belief that poetry can still shape lives, even as reality begs to differ. Set in Medellín, the film follows a poet in his fifties who, while grappling with personal disappointments and financial precarity, attempts to pass on his idealistic dreams to a teenage girl from a disadvantaged neighborhood. He discovers her while (drunkenly) teaching philosophy at a local high school. She writes poetry, but her aspirations are refreshingly grounded: she wants to be a nail artist. In one of the film’s bittersweet ironies, a local poetry festival that was meant to uplift her goes wrong, forcing the protagonist to confront the limits of his influence—not just over his student’s future, but also in the strained relationship with his daughter, who wants little to do with her self-proclaimed “failed poet” father.

Mesa Soto masterfully navigates the ethics of mentorship, the romanticization of art, and class tensions, all with an understated humor that never underlines its own presence: the kind of humor that doesn’t explain itself, because it doesn’t need to. And finally, the answer to whether one can live off of art? The film offers a clear “no” (as the director himself noted in a recent interview, “Vivir del arte es una utopía”), but does so with such warmth and wit that it feels more like a sigh of solidarity than a condemnation. For this balance of comedy and political insight, Un Poeta deservedly took home the Jury Prize in the Un Certain Regard section at Cannes.

7. Once Upon a Time in Gaza by Tarzan & Arab Nasser

Set in 2007, this film follows Yahya, a student, and Osama, a charismatic dealer, as they open a falafel shop that doubles as a front for their illicit activities. What begins as a clever hustle soon spirals out of control when their activities draw the attention of a corrupt local policeman. On this premise touching on survival, community, and resistance under extreme conditions, later comes a twist: Yahya is unexpectedly approached in a bar by a filmmaker who insists he has the face of a leading actor. Initially hesitant, as he’s never acted before (and the producer is equally unconvinced), Yahya is eventually cast as the protagonist in a biopic about a national hero. As he immerses himself in the role, the courage and defiance of the character he plays start to seep into his own life, and Yahya finds himself emboldened to confront the very corrupt forces that once kept him silent. The Nasser brothers earned the Best Director prize in the Un Certain Regard section at Cannes.

8. Lucky Lu by Lloyd Lee Choi

Presented in the Quinzaine des réalisateurs section at Cannes, Lucky Lu is promising feature debut from Lloyd Lee Choi. The film centers on a Chinese migrant delivery worker in New York City, played by Chang Chen, whose stolen e-bike sets off a somber exploration of urban survival, familial duty, and the elusive meaning of success. The theft takes place the eve of Lu’s family joining him in New York, and in this terribly short race against the clock, misfortunes follow one another: he loses his delivery job, the apartment he just fully paid rent in cash for turns out to be a scam, and old friends turn away from a Lu in need, as he tries to hide it all from his wife and daughter. Through its titular irony—Lu appears to be anything but lucky—the film interrogates what “luck” might look like. The final scenes, in which the family enjoys Chinese takeout in their new apartment, hint towards a gentle answer: luck might just be the ability to hold on to one’s community and self-worth, regardless of the circumstances. Choi’s work, as The Hollywood Reporter notes, draws inspiration from Italian neorealist film Bicycle Thieves. Yet Lucky Lu veers into its own terrain, capturing the everyday struggles of New York City immigrant life.

9. Eagles of the Republic by Tarik Saleh

Tarik Saleh’s Eagles of the Republic concludes his Cairo trilogy with a political thriller centered on George Fahmy, Egypt’s most famous actor, who is threatened and coerced into playing the lead in a state-sponsored biopic about President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi. Initially amused and self-important, George questions how someone with his looks and height could play a short, balding autocrat. But the regime’s request is not optional. Thus, what begins as a satire of celebrity ego turns into a study of fear and control under authoritarian rule. As he dons the military costume and delivers scripted loyalty, George is swept into the closed circuit of military power, and becomes a pawn in a political apparatus that uses cinema to rewrite national history. His affair with Suzanne, the Western-educated wife of the minister of defense, only tightens the trap. When an incident occurs during an official speech, the tone of Saleh’s film changes completely: the plot unrecognizably turns from the humorous vanity of the acting world into a shockingly violent political coup. With a $10 million budget, making it one of the most expensive Arabic-language films ever made, Sweden-based Saleh is able to build a critique of how regimes weaponize storytelling, and how even the most privileged can be crushed in the process.

10. Eddington by Ari Aster

If I’m leaving Eddington for last, it’s because I’m still not sure how I feel about it. Set in a fictional New Mexico town during the early days of the pandemic, it attempts to capture the chaotic social fragmentation of that time. Alison Willmore, in her Vulture review, notes that horror mixed with black comedy might be the only genre still capable of expressing our current moment. That blend does the works here, but it also contributes to a certain sense of incoherence. Topical, satirical, and grotesque, Eddington never seems to fully disclose its stance. The film centers on Joe Cross (Joaquin Phoenix), a small-town sheriff who insists on normalcy while the world unravels around him: his marriage is fraying, his mother-in-law is radicalized, and his rival (Pedro Pascal) is both mayor and ex-lover of his wife. The town’s culture wars play out through conspiracies and Facebook video posts—a force Aster successfully gives weight to, as if the internet itself were a character. Emma Stone plays Joe’s wife Louise, while Austin Butler, as an influencer, embodies the surreal extremism of the online world. With a cast that sometimes carries the plot, and raising important questions about power and delusion, Eddington proposes a rather messy storyline. But this may just be the kind of mess that speaks to the disorientation it depicts.

PS: I have to admit I haven't seen Jafar Panahi's Un simple accident, the Palme d'or winner, and which only based on the filmmaker's own story is already a laudable case of resistance through cinema. I'm waiting impatiently to see it in cinemas this fall, along with others that I inevitably missed in Cannes, where everything happens everywhere all at once. ∎